I was reading my journal and realized that I sounded like a broken record. At every opportunity, I talk about compounding and exponential growth.

I think I was still internalizing the concept for most of these past 3 years, hence my eagerness to pattern-match things around me to "exponentials."

Now, I'm confident I've internalized it. I can explain it at different levels of abstraction, understand where it applies (and where it doesn't), and even feel something when I close my eyes and imagine it.

However, I noticed there's a different concept cloud that has been growing in my headspace. I'm less eloquent when I talk about it and sometimes even have trouble articulating it.

The concept cloud is: craft, focus, patience, and quality.

This post is my attempt to take a step (however small) toward understanding how these concepts relate and what they mean to me.

Rethinking art

It's hard to point out the exact moment these seeds were planted in my mind, but I think it started after I changed how I viewed art.

I used to think that art wasn't a worthwhile pursuit.

I could admire the aesthetics of a painting or the skills of a composer but saw no intrinsic value in art.

It wasn't like science or engineering, which pushed society forward. At best, art was an occasional source of entertainment. A nice distraction.

Over the years, my life changed and at some point, I came across this quote from Alain de Bottom while reading his book:

Art, Arnold insisted, was 'the criticism of life.'

What are we to understand by Arnold’s phrase?

First, and perhaps most obvious, that life is a phenomenon in need of criticism, for we are, as fallen creatures, in permanent danger of worshiping false gods, of failing to understand ourselves and misinterpreting the behavior of others, of growing unproductively anxious or desirous, and of losing ourselves to vanity and error.

Surreptitiously and beguilingly, then, with humor or gravity, works of art—novels, poems, plays, paintings or films — can function as vehicles to explain our condition to us. They may act as guides to a truer, more judicious, more intelligent understanding of the world.

— Alain de Bottom on "Status anxiety."

This quote made it click for me. Probably because when I was reading this, I identified with some of the symptoms of a "life without criticism."

It made me understand that, at its core, art promotes reflection.

We feel emotions that we wouldn't otherwise feel listening to music, and we learn more about ourselves in the process. We empathize with characters when reading fiction or watching a movie, and we take their lessons as our own. We see a painting and might feel inspired to apply the same level of craft to our own lives.

After this realization, I changed my views on art. It's not about appreciating "the greats" or signaling that I'm "cult." It's about learning more about myself and my journey.

For example, I learned a lot about appreciating my own journey after reading "Kafka on the Shore" and "The Alchemist." Every time I listen to a great song, I imagine the exhilarating feeling the composer must have felt when they put all the pieces together to produce something great out of thin air and I think to myself "I want to feel that too!"

This shift in my view of art was important because, after university, life became way less linear. Amid a sea of possibilities, I started to question what should I be pursuing and how to spend my time. Art became a tool that I could use to help me navigate life.

Embracing craftsmanship

One day in 1671, Christopher Wren observed three bricklayers on a scaffold, one crouched, one half-standing and one standing tall, working very hard and fast.

To the first bricklayer, Christopher Wren asked the question, “What are you doing?” to which the bricklayer replied, “I’m a bricklayer. I’m working hard laying bricks to feed my family.” The second bricklayer, responded, “I’m a builder. I’m building a wall.” But the third bricklayer, the most productive of the three and the future leader of the group, when asked the question, “What are you doing?” replied with a gleam in his eye, “I’m a cathedral builder. I’m building a great cathedral to The Almighty.”

— Parable of the three bricklayers.

The story above has many versions. I first came across it in Paul Getty's book "How to Be Rich." To me, the moral is: while the object of people's actions might be the same, the way they see what they're doing also matters. A lot.

I've thought about it in my own context. Just like the first bricklayer, I could see myself as an engineer writing code for a living. However, life is much more colorful when I look at it like the third bricklayer.

Through Openlayer, the startup I've been helping build for the past 3+ years, I'm serving our users. I'm helping them build reliable AI systems, which will be deployed and directly impact many people's lives. I'm spending my time and energy trying to create something I genuinely believe should exist in the world and, hopefully, make it a little better.

The process was far from sunshine and rainbows. This is a lesson that I learned after repeatedly hitting a wall and questioning what I was doing with my life. I learned to accept that the end results are not fully in my control. However, I actively decided to dedicate every inch of me to the parts where I have agency.

The ideas of taking responsibility for what you're building, focusing on the quality, and continuously improving are relatively well-known in software, via the software craftsmanship movement. Here, I really liked the book "Software Craftsman" by Sandro Mancuso.

Focusing on the craft helps me quiet my mind from all the noise and obsessively focus on what I have control over.

(Focus)^Patience

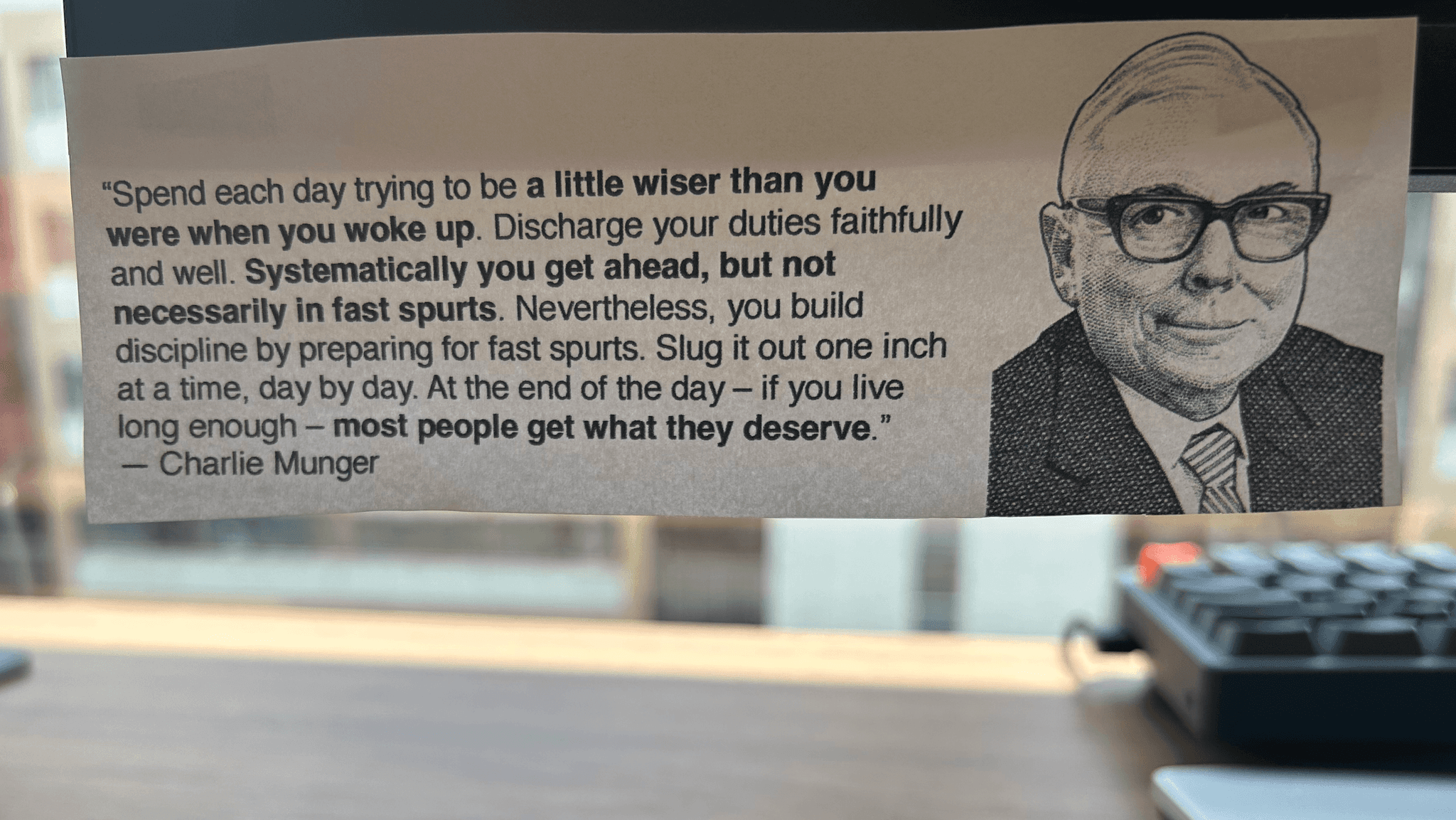

I have this Charlie Munger quote hanging on my monitor and I read it every day. I like it because it reminds me of the important (yet often overlooked) idea that things take time to happen.

When I look at my group of ambitious friends, everyone seems to job-hop every 1.5-2 years. They are all considered overachievers but are they missing something? Or am I missing something?

Both sides of the argument have their merits and if something is objectively bad for you, then by all means, jump ship. However, I think people give in to impatience too quickly. I'm not immune to impatience but I've been learning to ignore the urge when I feel it rising.

I think we're all impatient partly because we crave for signals that tell us we're on the right track. In school, for example, the "signal" came as test results. Every few months we would get a score that unambiguously told us whether we were making progress. In life, the signs of progress are less clear. Maybe you earn more money every time you job hop and that gives you the impression that you are moving forward. Maybe you are interrupting an exponential.

Patience matters, but it's not the only piece of the puzzle. You also need focus.

Focus is a force multiplier on work.

Almost everyone I’ve ever met would be well-served by spending more time thinking about what to focus on. It is much more important to work on the right thing than it is to work many hours. Most people waste most of their time on stuff that doesn’t matter.

— Sam Altman on "How to be successful."

I've listened to the life stories of enough people I admire to understand that what set them apart was their relentless focus sustained for a long time. Charlie Munger is obviously an example. James Dyson is another. It took him 14 years (and 5,127 prototypes) to develop the Dyson vacuum cleaner.

I came up with the expression (focus)^patience ("focus to the power of patience") to remind me of both and I'm actively trying to apply it to my own life.

Quality

In a sense, "quality" is the end result of everything I've been talking about so far.

Quality materializes beauty and is the byproduct of craftsmen applying deep focus for a significant amount of time.

I'm so sold on this idea that I want to produce (through my work) and consume things that are "high quality." If you pay attention, the world has many products that are way superior to the average.

For example, Herman Miller chairs. You have every right to disagree with their price, hate their design, or dislike their ergonomic choices. But you cannot say it's low (or average) quality.

I respect this. It means someone went out of their way to think deeply about something. They fought the human urges to finish things quickly. They've built something of high quality and it shows.

Forward

Reflecting on all of this, I've come to see life as less about chasing quick signals and more about nurturing depth.

I started by viewing the world through the lens of exponentials; now my glasses received an upgrade. I'm equally fascinated by the slower, subtler art of craftsmanship, and commitment to quality. At first sight, they seem conflicting. In fact, they have great synergy.